The Unknown Warrior

This is story of how the " Unknown Warrior" was selected and finally laid to rest at Westminster Abbey:

And

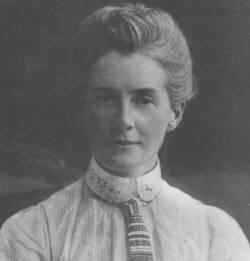

Edith Cavell who sheltered British soldiers by funnelling them out of occupied Belgium to neutral Holland.

Followed by World War I - If You Shed a Tear ...

You are invited to down load the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR”.

THERE IS NO CHARGE.

On the stroke of midnight on 7 November, 1920, Brigadier General

L. J. Wyatt, General Officer Commanding British Troops in France and Flanders, entered

a hut near the village of St Pol, near Ypres in northern France. In front of him were the remains of four bodies, all of them lying under Union flags.

Earlier that afternoon, the bodies had been disinterred from unmarked graves in each of the main battlefields, the

Aisne, the Somme, Arras and Ypres. Four blank crosses had been chosen from the forest of crosses that now covered the shell-pocked French landscape.

As well as coming from unmarked graves, the bodies all had to belong to soldiers who had died in the early years of the War. The orders given to the

exhumation parties were very clear on this point. The bodies had to be as old as possible in order to ensure they were sufficiently decomposed to be

unidentifiable. Wrapped in old sacks, the four dead soldiers had been brought to St

Pol, where they were received by a British clergyman and two undertakers who

had travelled to France for the occasion. There, the remains were examined to make sure they bore no identifying marks, then placed inside the hut for

the remainder of the day.

In some reports of what happened next, Brig Wyatt was described as being blindfolded. There were also reputed to have been six bodies rather than

four. However, the brigadier makes no reference to being blindfolded in his account of what happened, and insisted that he saw only the remains of

four bodies when he stepped into the hut as midnight struck. There, the brigadier lifted up his lantern to take in the scene. Then he simply reached out and touched one of the Union flags. That was it; he had

made his choice. He had picked a body to go inside the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior.

![[ "Unknown Warrior" ]](The-Unknown-Warrior.gif)

![[ “Let this body – this symbol of him – be carried reverently over the sea to his native land.” ]](unknown-soldier.gif)

![[ On the morning of 10 November, the coffin was taken to Boulogne. ]](unknown-soldier_2.gif)

![[ HMS Verdun. ]](HMS_Verdun.gif)

![[ King George V ]](George-V.gif)

![[ A large slab of Tournai marble was then placed on top ]](Tomb.gif)

![[ Picture shows exhumation of Miss Cavell. ]](Edith-Cavell.gif)